THE EMERGENCE OF THE GREEK-AUSTRALIAN FAMILY 1930s-1960s: THE CREATION OF SOMETHING NEW.

A second generation Castelorizian boy, 1927 dressed in a traditional dress by his mother. The photograph was sent to his grandparents in Castelorizo. The dual identity of second generation Castelorizian born in Australia is captured by this photograph.

Introduction

" Dispassionately, Achapi remembered sitting down with Maria on he potato sacks forever peeling, Mumma bending down under the counter and throwing the fish in batter into the basket an down into the fat while Pappa watched the fat rising like the bubbles above his diving suit, grey and slow, and tried not to cough. It was lonely even in that close family unit with Mumma and Pappa only a few feet away. They were always too busy cooking and preparing, then sleeping while Pavlos sat upstairs with his school books, never protesting he wanted play because he knew, he had always known that something was expected of him. Kerry Walsh CIRIGO KYTHERA) A Novel. " (0)

In the preceding chapter the life of the early Greek arrivals has been discussed. The original Kytherian and Castellorizan settlers came to Australia as young men seeking better economic opportunities, possibly adventure and political sylum from the constant Turkish invasions and bombings of the island of Castellorizo. In order to survive they needed a well-organised and supportive Greek community. Thus they developed a system of business promotion and patronage that resembled the extended kinship system that existed on their respective islands of origin. Once married the early settlers brought up their children in Australia in accordance with the family practice back on the island. However the second generation Kytherian and Castellorizan parents did not retain the traditional Greek family structure. The 'Greek-Australian' family that emerged in the last 1950's, 60's and 70's did not resemble the Greek family in Greece either on the mainland or the islands. It had distinctive features which were not evident in Greece. These features were developed in Australia and were party a product of the charges that Australian society had undergone after the Second World War with rapid industrialization and urbanization. (1) The insular and restrictive, predominately British society that existed before

the war was altered, not only in character but also in composition with the advent of large-scale migration to Australia. "This change in ethnic composition arose from the fact that, of nearly two-million settlers who arrived between 1947 and 1966, over 60% were non-British... The sheer size of the post-war influx has effected lasting changes in Australian society". (2) The society became more flexible, attitudes and ideas about women and women's employment changed though not drastically. The changes which occurred affected to a large extent the second generation Kytherian and Castellorizan families. Apart form the influences within the society, the change in status from working to middle class which occurred from the first to the second generation also affected the nature of the new Greek-Australian family and also accounts partly for its features. The childhood experiences of the second generation growing up in Australia also determined the character of the new 'Greek family' and it is their perceptions in particular which offer a fuller understanding of the evolution and change of the Greek family in Australia.

The children of the Kytherians and Castellorizans have an acute and intense perception of what life was like growing up in a Greek family within an Australian environment. Their discussion of their own upbringing adds an extra dimension to the story of Kytherian and Castellorizan family life in Australia. They were the ones who vividly saw the disparity between the Anglo-Saxon and Greek life-styles, not their parents. Hence the vision of Greek family life in Australia, presented by the parents in the preceding chapter, does not convey the 'starkness' of the migration experience, as it was perceived by the children of the early immigrants. The parents had not been exposed to two world views from childhood. They had come out with a secure image of what constituted Greek family life and were not forced to question it.

Rural Environment

Life presented few contradictions or ambiguities for them. It was simple and obvious: the Greek family would function and survive in Australia as it had in Greece, and the children would be brought up according to the Greek family tradition, without and changes. The parents were able to retain this secure image and implement it because Pre-war Australia was congenial to and did not impinge upon the Greek peasant family. The Kytherian and Castellorizan Greeks ahd come from a rural envirnmnet to a predominatly rural economy (3) which had not as yet experienced large scale industrialisation and urbanisation which was to leter challenge and devide the traditional roles within the post-war Greek family in Australia. Thus for the pre-war Kytherian and Castellorizan parents there was no necessity for adaptation nor was it ever contemplated. The parents were in a different position from their children, for they had accepted the fact that they were 'foreigners', they know that they might not be totally accepted, or that they might not be accepted at all and had resigned themselves to the situation. If the host society showed friendliness and warmth, it would be appreciated and accepted, if not, thn this would also be reconciled. They could not afford the time to stop and worry about being 'liked' or accepted, their main concern was to give their children the economic security that they had been deprived of in theor own country. 'Steven Adams', a twenty-six year old Greek Australian of Kytherian descent born in Grafton, NSE, explains their position.

" ...They came out here, they coudn't ask any fundamental questions..they didn't have to ask the meaning of life ...the meaning was quite clear to them, that they had to work very hard and better themselves for their kids...which they did very successfully and they took it out on their kids in the sence of the whole familty thing...they tried to transpose a frozen version of Greek morality and mores, ofcourse it doesn't work and it does confuse the kids...they've always got this DUALITY between their outside life and their home life, which is always very different...they've given sets of PRESCRIPTIONS by their parents instead of guides... " (4)

Prejudice

The children had multiple pressures placed upon them. Unlike the parents, the children did not have a passive acceptance of their lot. They were born in Australia and resented not being accepted as equals and could not easily reconcile their position, particularly the Castellorizan children who grew up in the migrant suburbs in the city in late 1930's and 40's. These children were exposed to prejudice in the schools, subject to assaults in the streets, and also experienced the racism directed against their parents (such as smashing of their shop windows) and were unable to find employment in the late 1930's and 40's because a Greek name meant instant refusal. Furthermore the children had to also cope with the duality involved in being part of two cultures which were totally different.

" I think we Australian born Greeks had double traumas - we were trying to live in two worlds which were completely different, and I think we had more hang ups and more conflict growing up because of that than if we either in Greece, living there, or being Australian - growing up the Australian way of life. But when you're in the middle of two worlds I think it's very difficult... " (5)

They had to undertake dual roles: one of being a Greek child in a Greek family and fulfilling their obligations to the 'family' and the other of surviving and succeeding within the wider Australian society. A.W. Green studying some Greek-American students in a New England college, commented extensively p.n. the mental problems of the second generation.

" ... they are cut off from home ties in a somewhat alien world which regards them as 'inferior', at the same time parent are pushing them to 'succeed', a striving which is regarded by the parents as a means of improving familial status, but which increasingly for the Greek students becomes a hope for improving individual status. Out of this complex crisis the damaged self-conception, which is the psychological mark of the marginal man. " (6)

Whether the second generation children suffered from a damaged self-conception as a result of the pressures placed upon them is debatable, however that they were confronted with two opposing world views, one which was familial and the other individual is indisputable. Western, Anglo-Saxon society is based on the concept of 'individualism' where men has become an autonomous being and society exists for the fulfillment of the individual. However the Western concept of individualism becomes irrelevant and quite meaningless in

Familiy Obligations

traditional Greek society which stresses the importance of loyalty to a group and where the very person exists only because af these groups.

" ... Self-definition is in terms of group relatedness and not as an individual; existence as an individual separate from these groups is inconceivable. Nothing demonstrates more dramatically the absence of the notice of an autonomous individual than the absence of a word in Greek fcr privacy. The frequently heard statements of pity regarding individuals benefit of family and/or fur for n the village reflect the belief that such a person is incomplete. " (7)

In Greek society a person cioes not possess an identity of his own which is separate from his family. "Who and what on is, is answered by referring to one's position within membership groups. t Who am Il. will elicit a response stating family, clan, village and specific status within these groups". (8)

Furthermore, in Western society, what an invidioualy l will be and do is not PRESCRIPTIVE, but is determined by the individual for himself. Whereas in Greek society, "self-worth is judged by the person and by others in terms of how well the PRESCRIBED obligations and loyalties are fulfilled, and self-fulfillment is attained by performing well the assigned role within the membership groups". (10)

The Kytherian an dCastellorizan children were therefore compelled by virtue of their culture to fulfill the obligations to their family otherwise they would inflict 'shame' on themselves and their family.

'In Greek culture, shame is the psychological device employed to ensure conformity, and shame is the emotion a person's transgressions engender in him. A Greek is not responsible to himself, but to the group of which he is an integral part. And shame is the psychological penalty for behavior inappropriate vis-a-vis the group'. (11) Hence there was a lot of pressure for young Kytherian and Castellorizan children to conform to Greek traditional norms and family organisation. Thus Castellorizan girls were not allowed out otherwise the family would be shamed in the eyes of the community. The community exerted a lot of control over the behavior of the family members for if they deviated they would suffer the 'ridicule' of the small Greek community in Sydney. 'Ridicule' like 'shame' (entrap) is a closely

related socializing device where "adults, group relatedness and group identification is reinforced by evaluating actions in terms of whether they will bring 'ridicule' (rezilepsun) upon the individual and hence the entire group". (12) While the psychological device employed by Western society ensure conformity to ethical standards, 'individual guilt' is a personal feeling independent of external social sanctions. (13)

Thus Kytherian and Castellorizan children were faced with different world views, which constantly presented a series of contradictions and ambiguities. American studies of second generation Greeks suggest that the situation which the children of the immigrants faced inevitably leads to 'conflict' within the family.

" ... with the oncoming of the second generation (the immigrants' children), the highly ethnocentric, traditional, and folk-oriented outlook of the first generation subculture was challenged. Culture conflict between parents and children was inevitable. Yinger referred to this phenomenon as 'contraculture. " (14)

Yet 'conflict' is not evident within the Kytherian and Castellorizan families who were interviewed. The second generation Castellorizan children grew up in an excessively strict family environment, yet in their reminiscenes of their childhood and upbringing 'conflict' with their parents is not mentioned. Admittedly they tended to romanticize their upbringing to a certain extent and remembered what they now consider to be the good points in their upbringing. 'Peter Politis' born to Castellorizan parents, I can only remember good things about it and that is why I love it". (15) Participation in large-scale family picnics conducted in the 1930's an d40's are looked back upon and praised by the second generation but at the time they were probably a bit resentful of being forced to attend them.

Anxiety over not being allowed out is mentioned bu tender any conflict between children and parents, as a result of it. Nevertheless te Greek family as a result fo the children's exposure to two cultures, but that this conflict produced what American sociologists have called the "marginal man" is an individual who "through migration, education, marriage, or some other influence leaves a social group or culture without making a satisfactory adjustment to another, finds himself

Hybrid Culture

on the margin of each but member of neither". (16) Robert E. Park describes the "marginal man" as "a cultural hybrid, a man living and sharing intimately in the cultural life and tradition of two peoples/... which are never completely interpenetrated and fused". (17)

The American study dealt with second generation migrants at ta particular point in time. The oral history interviews of the Kytherian and Castellorizan second generation generation in Australia have shown that a fusion had definitely occurred and they would consider themselves to be a member of both cultures. The second generation Greek families had taken elements from the Greek and Australian familial traditions and had incorporated them into their own family and in the upbringing and had incorporated them into their own family and int he upbringing of their children. thus a synthesis had occurred between the Anglo-Saxon and Greek familial traditions forming a 'hybrid culture',. George Kourvetaris in his three-generational study of the Greek family in America also identifies the existence of a 'hybridculture' amongst the second generation Greek American but maintains that the second and later generations of Greek Americans, challenged the importance of the family. (18) The second generation Kytherian and Castellorizans did not challenge the Greek family and Greek culture and tradition, they changed and modified the Greek family but it did not cease to be an important institution in the second generation and beyond. What occurred by the second generation is the creation of a completely new subculture within the wider Australian society, a Greek-Australian culture which accommodated the two cultural traditions. This new subculture allowed for the retention of 'Greekness' and the survival of the close-knit family network. Glazer and Moynihan investigatting ethnic groups in New York city in the early 1960's documented the creation of this new subculture. They observed that

" ... as (ethnic) groups were transformed by influences in American society, stripped of their original attributes, they were recreated as something NEW, but still as identifiable groups. Concretely, persons think of themselves as members of that group, with that name, they are thought of by others as members of that group with that name; and most significantly, they are linked to other members of the group by NEW attributes that the original immigrants would never have recognized as identifying their group, but which nevertheless serve to mark them off, by more than simply name and association, in the third generation and beyond. " (19)

The new Greek American family that emerged certainly did have new attributes which the first generation Kytherian and Castellorizan parents would not hate dreamt would have occurred but nevertheless accepted.

Greek 0rthodox religion and Greek language were no longer the main distinguishing features of the Greek family, with the emergence of the second generation family, major changes had been wrought upon Greek family tradition. Greek morality and authority had been changed. The daughters were no longer withdrawn from school from an early age and protected as they had been in the 1930's and 40's, instead the girls were allowed to date freely like their Australian counterparts, their marriage was no longer arranged by the parents but were similar to Australian patterns of courtship and marriage where the children chose their future spouse on the basis of romantic love. The second generation parents had been influenced by the Australian society within which they had been born and raised ard felt that "there's nothing wrong with these aspects of tee Australian way of life. I didn't agree with everything. Then on the other hand I could see there's nothing wrong with these particular aspects of Greek life". (20) Changes in family life had also occurred in Greece but these changes were very few and limited and only occurred in the metropolitan areas not the rural villages and islands.

Although changes were introduced into Greek family life by the second generation, continuities between the different generations of Greek in Australia also existed. The second generation Kytherian and Castellorizan children maintained aspects of Greek family life such s respect for elders, the belief that parents hould be looked after by their children and not place din an old people's home, attendance at the Greek Easter service and preservation of the Greek wedding engagement and christening ceremonies and naming of the eldest son after the husband's father. However the most important thing the second generation Kytherian and Castellorizan parents wanted to inculate within their children was an awareness of their Greek background and heritage: "... they went to Greek Sunday school, they realized what their background as and it gave them a sense of belonging and I was very pleased about that... they're aware from where they came and what being Greek means to their grandparents. I want them to know that I think that's very important". (21)

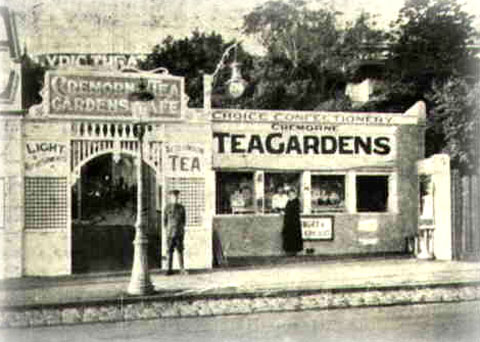

Cremorne Tea Gardens owned by Theodor Politis who can from the island Leukas to Australia in 1901. He set up the Tea Gardens in the Melbourne of St Kilda 1916

The café pictured was owned by Mr. Antoniou Levakatsas born on Ithica in 1863. The café was in Melbourne where Mr. Levakatsas was the president of the Greek community in 1916

Paris café Melbourne 1916 also owned by Anonitou Levakatsas.

Their insistence or endogamy - that their children should marry Australian born Greeks was done not out of loyalty to Greece, but out of loyalty to the grandparents, so as to create 'links' and keep the extended family together. Nevertheless, the second generation Greek-Australian parents no long thought of themselves totally as Greeks but as Australian born Greeks, who respected their Greek culture and tradition but simultaneously felt that they could live in no other county but Australia. "Basically, I love the fact that I'm born here, because I think Australia is the best country in the world, even though I haven't been overseas". (22)

Unpleasent Memories

Regardless of their allegiance to Australia, the second generation had experienced prejudice and rejection which affected their attitudes and to a certain extent determined the nature of the 'Greek-Australian' family that emerged. The Castellorizan second generation growing up during the 1930's and 40's had unpleasant memories of childhood: of having to leave school early to work in the family business in an inner city slum, a ghetto environment where they were deprived of any pride in their Greek heritage. 'Peter Politis', a 50 year old second generation Castellorizan born in Sydney in 1928 captures the sentiments of the young Castellorizan children of that era.

" ... we lived in a hell-hole in Redfern with a very poor standard of Australian around us... we were very glad to get out of there, Redfern was a very tough area then - before the war, right through the Depression, and Europeans were not very liked in Australia at that stage - tolerated that's about all. " (23)

Southern Europeans were certainly not well liked before the war and the Castellorizan children growing up in the city were particularly vulnerable to abuse. The Castellorizan boys especially who were allowed more liberty than the Castellorizan girls were quite frequently the subject of assaults by neighborhood mobs who found the Greek children convenient scape-goats. "... those days were very rough, each suburb have a mob... when the mob felt like taking it out on somebody they used to take it out on the Greeks, me and me mate came in again". (24)

In the schools from the late 1930's even up till the early 195O's, there were very few Greek children and those who were there experienced rejection

" ... when we were in primary school the children used to ridicule us and call us aboriginal, because our skin was darker, not that we spoke a different language, we were a bit different from them... " (25)

As a result of this sort of experience the Australian born second generation sent their children intentionally to schools with a high migrant population even though many could afford to send them to private schools.

" We've sent them to... Kensington Public School... on purpose, my reasons were that they would mix in with other children who are from Australian educated parents but Greek grandparents. Also there are a lot of new Australian children there, they are hearing the language constantly even at school, and it makes them feel that they are not outsiders by going to Greek school... " (26)

The second generation Castellorizan children experienced many bad moments and they felt the effects of prejudice even more intensely than their parents. Thus it is no wonder that they wanted to spare their children the pain involved in such encounters.

'Peter Politis', a second generation Castellorizan explains that the fish-shop his parents had in the 30's and 40's in Redfern had the front window smashed every six months. (27) 'Peter' remembers vividly the environment he grew up in and the many episodes he witnessed as a child growing up in a Greek household in Australia. 'Peter's' mother, was a very physically strong woman because she had grown up on a farm on the top of the mountains in Castellorizo" and they were tougher than men". She could pick up a "140, 150 pound bag of potatoes, put it her shoulder and walk away with it". (28)

Even as late as the forties in Australia, the Greek shop still had to have a leg from a chair underneath the counter for protection and 'Peter's' mother because of her strength,

" used to be the Sockeroo, she used to close the door and underneath the counter she used to have a leg of a chair, and what she used to do to those fellas was unbelievable, she used to split heads, left right and center... because they'd threaten Dad with violence... these were drunks, no reason at all, walk into the shop, ask for things for nothing, when they wouldn't get it then they'd come around the counter and cause trouble but I remember one incident there, I suppose... er... I was thirteen or fourteen years old at the time and this two man came into the shop using filthy language, very abusive to Dad, just drunk, calling us Dagoes... So with this particular incident this woman came out with ll the abuse in the world and my mother came out and gave her a shove to push her out of the shop, she got up and started swearing at Mum, again Mum pushed her out of the shop, Mum couldn't speak English, just one or two words like Hello and Goodbye, so couldn't get anywhere with her so she grabbed hold of her long hair, took her outside and outside of our place was a telegraph pole and she cracked her skull and she lifted her up again and the ambulance came and took her away. But that woman where she got back because she only used to live down the street, every time she'd pass and see my mother 'hello Mrs. Con, how are you Mrs. Con, lovely day Mrs. Con' and that is a fact, we had some very bad items there and we were glad to get out of there out of Redfern. " (29)

The young Castellorizan children seeing their parents involved in such unpleasant circumstances felt compelled to succeed financially and quickly move out of these inner city migrant suburbs in Sydney into middle class areas. They became strongly committed to social mobility, which they achieved within a generation. Mobility occurred not only as a result of experiencing prejudice but in an effort to increase familial status. The second generation Castellorizans had the 'means' of achieving social mobility. They constituted a 'shop-keeper class', independent businessmen who were able to achieve through hard work and long hours the resources to move. Whereas the post-war Greek migrants who were simply 'workers' in factories were not in a position to do so. The second generation felt that the prejudice directly against southern Europeans before the war was a result of economic envy,

" ...I suppose there wasn't a lot of work then even for the Australians at the time and they resented somebody else coming along and doing perhaps a little better than they buth the situation is that the Greek especially, was prepared to work 90 perhaps 100 hours a week, whereas the Australian wasn't prepared to do that... " (30)

Although economic concerns partly explain the resentment displayed, it does not totally explain the magnitude of the Australian reaction towards the immigrants. Australia before World War II was an insular society, which had not as yet experienced diverse customs and ideas and was very fearful of anyone who was different. The prejudice reflected "the dislike of many British-Australians for persons whose economic activities cut very little across their own but whose way of life was different". (31) The second World War produced some changes in the attitudes of the Australian population, but how widespread these changes were is not known. Many of the early Castellorizans felt that after the War there was indeed a change in the Australian attitudes towards them. Australia could no longer remain totally isolated from the rest of the world:

" ...the Australians went overseas, they saw a it of Europe, the Americans came over here and they saw them and they realized that Australia is not the only nation in the world, other places exist which are more educated... we were promoted between 1930 and after the War from 'Dago, bloody dagos', we became 'New Australians'. And now we are 'old Australians'... " (32)

There is a bitterness in the description of the change given by the first generation of Castellorizan migrants. They were resentful of the country's refusal to acknowledge the validity of other cultures.

It appears that they were also aware the political implication of the change in the epithets for the immigrants. Nevertheless it was generally felt at the time that Greece's effort in the Second World War and the Australian and Greek troops fighting together in Crete created a sense of unity and respect between the two countries.

'Bill Andrews' a second generation Castellorizan who fought in the Second World War was slightly more generous in his description of the change in Australian attitudes as a result of the War:

" ...there was a change... a very gradual change but the very big crux came during the War when after Italy joined the AXIS forces and they were taking country after country and they came down through Albania and Yugoslavia and then the next thing they thought they were going to walk over Greece and Greece held them off with their pea rifles virtually they pushed them back and back and the Australians realized there was a big difference between the Greeks and Italians, then there was a big admiration for them and then when they fought valiantly with the Australians in Greece and Crete and all the stories came back how the Australians were being treated by the Creeks. A lot of the prejudice diminished hull: there even to this day, there is stil1 prejudice I know there are times I feel, but nowhere near the same degrees. " (33)

Regardless of the change that had taken place in Australian attitudes towards migrants as a result of the War, the Castellorizan children before the War had to contend not only with discrimination in their outside lives but they also had to maintain a dual identity. They had to conform to the strictures of Greek society as well as attempt to succeed in the wider Australian community. Although the young Castellorizans were forced to conform to a life-style which was restrictive and tightly-controlled, they did not rebel against their parents. They accepted their parents definition of Greek family life.

" ...we grew up in an environment, sure, we argued with, our parents, we gave our point of view - but we never over went against them. If Mum and Dad said 'no' you can't go there, that was it. We accepted it. " (34)

There were disagreements but there was no hostility or conflict within the family between the children and their parents, even though the young Castellorizan boys tended to be rebellious whenever dowries and 'proxies' or arranged marriages were mentioned. Marriage was arranged by proxy in those days and was an activity conducted by the parents and did not involve the children. It was the custom during that period for Greek families with eligible daughter to make an offer of money for particular young men, in effect pay a dowry to the groom. This was done with the services of a 'proxenitra' or matchmaker, usually a relative, who would act as a liaison between the two families and take care of all the business arrangements. Although the Castellorizan boys laughingly proclaimed that they were "a good catch" (35) for "...everyone got a dowry in those days. There was one girl giving me a thousand pounds. I had some very nice offers", (36) they still veered away and refused to be involved in any arranged marriages. They were beginning to be influenced by the Anglo-Saxon ethos of 'falling in love and choosing your own wife".

" ...I wasn't married till I was 36. The reason was if Mum opened her mouth on a proxy I'd just walk out. I was just not interested... I wouldn't ask, I'd just walk straight out. I just wanted to get to know a girl, to meet her, to understand a girl and like her for herself. " (37)

In 1941 the N.S.W. government declared 'Greek Day' celebrations in honor of the heroism displayed by the Greek nation in warding off the NAZI invasion of the country during the second world war. The celebration was aimed at raising money for the Australian war effort.

During the Greek Day celebrations, the N.S.W. government allowed official marches to take place through the streets of Sydney with young Greek men in their national Greek costume. In the picture there is a young Castelorizian girl offering her help for the Day in George Street in Sydney 1941.

The appeal of the Greek day celebrations reached the N.S.W. country towns and many of the Kytherian families contributed to the appeal. Pictured here are the Greek families in Tenterfield N.S.W. participated in the Days celebrations.

'Proxy' Weddings

Most of the second generation Castellorizan men who were interviewed married at a slightly older age. and had chosen their own wife, without their parents being aware of it. They had seen their future wives either at a Greek Christening or wedding and had managed to steal a moment with them alone to ask them to get married before going through with the formal proxy arrangement.

Thus 'Jimmy Papadopoulos' having only seen his future wife once before and meeting her again outside the Sydney fish markets asked her to get married. If she agreed he would arrange for a proxy to take place without the parents knowing that they had discussed it amongst themselves: "He asked me on the quiet, everything was on the quiet. He said 'would you marry me if we do the necessary proxy things'". (38)

After the proxy had taken place, the second generation Castellorizan couple growing up in Australia in the 1940's were forced for the sake of the parents to go through with the traditional Castellorizan engagement and pre-wedding rituals. Although they did not have to follow the rituals completely they still had to participate in the fundamental events. They participated in a religious engagement ceremony 'aravones', where the 'nifi', bride meets the 'gambro' groom, supposedly for the first time. After the engagement they had the 'krevati' or bed-ceremony where they show the girl's 'prika'/dowry. After the 'krevati' they have the 'savatovratho', the Saturday night before the wedding where they 'kapnisi'/smoke or burn insense over the wedding clothes and they wish the couple good luck. Then they had the 'Kiriaki proi'/ Sunday morning when they 'stolisi'/adorn the 'nifi'/ bride and they dress her for the church ceremony. (40)

" Mrs. Vanessa Politis, a second generation Castellorizan woman commenting on the Castellorizan wedding rituals she participated in explains that's the way we had to have it... They organised everything, really we didn't have a choice... I don't like 'Krevatia' and I don't like the celebration of the night before... When my daughter gets married I don't think she'll have either. " (41)

Arranged marriages were widespread amongst the Castellorizan community before the Second World War, for contact between the sexes was not acceptable and social life was strictly supervised. Young Castellorizan girls in particular were not allowed anywhere without a

Pre-Marital Sex

family member and then usually only with the patents. Mrs. 'Michelle Kiriakopoulos' a Greek-Australian of Castellorizan descent born in Perth, in 1921, exclaimed:

" It was just like being in a goal... You weren't allowed go here, you weren't allowed to go there. If you saw a boy in the street, you weren't allowed to talk to him... mother would have slit my throat! " (42)

It was in this one area that the young Castellorizan girls were hostile. This was the part of their upbringing they resented the most and which caused them much inner turmoil but they nevertheless accepted it.

" ...we weren't allowed out, and if girlfriends used to ask, we just used to say 'we can't go out with you, we've got a steady boyfriend' and they used to believe it, you know never used to like to say I'm not allowed to go out. " (43)

Not only were Castellorizan girls not allowed out but were also forbidden to work outside the family home, and were usually, but not always, excluded from working in the family business. Mrs. 'Stacy Mavromatis', a Castellorizan woman born in Sydney explained "I finished (school) in third year... I wasn't allowed to go into a career - I was allowed to go to Sydney Technical college where I learnt dressmaking, I never worked... I had to stay home and help". (44)

Even though Castellorizan girls were severely secluded in pre-war Australia, Australian society before the Second World War was not an open and liberal-minded community. British-Australian girls although allowed to date and work in the city in shops, were also supervised by their parents, but of course, not to the same degree as the Castellorizan girls. Pre-war Australia was still very much a rural society, which did not condone pre-marital sex, and woman who had chi dren outside marriage were branded as immoral. Young British-Australian children could not leave home and live in a flat as this act would have been condemned by the society. Children remained at home until they were married. The Castellorizan parents were scared during the war to allow their daughters to continue attending high school because of the arrival of the Americans "...there was the war and you couldn't allow the children to continue (school) because there were the Americans and you were afraid at night to let the children...". (45) But the Australian parents were also concerned about protecting their young girls from the Americans, and many girls were advised to catch transportation into Sydney rather than to walk to work because of fear about the Americans with money in their pockets and only one thing on their minds. (46)

Kytheria café in Bega N.S.W. Circa 1950s

Entertainment in country town was limited for the Kytherians but families often went on picnics between themselves. Bega N.S.W. 1950s

Kytherian picnic in Bega N.S.W. Circa 1950s.

Furthermore, although Castellorizan girls were not allowed to work outside the family, there were not many jobs available for women in pre-war Australia, especially since the country had undergone a Depression. The British-Australian women, particularly the ones who lived on farms were forced to stay and help on the farm and look after the family for employment was difficult to find elsewhere, and it-was not thought correct for a young girl to leave her family to go to the city. (47)

Apart from the nature of pre-war Australian society the surprising aspect of the young Castellorizan women's attitude to their upbringing was that although they were strictly supervised and resented being so; they looked back romantically and admired the type of family social activity they were forced to attend. "...Dad was the type that made sure we had enough things going for us, some days we'd go to the beach all the families and all the cousins, big groups and truly we'd have a marvelous time, I can't see that happening now". (48) The first generation parents had made sure that they did not feel the need to look outside the family for entertainment.

The second generation Castellorizan men also looked back upon the large-scale family picnics with a favorable eye. But in general the young Castellorizan boys veered away from such family gatherings and mainly spent the early years of their lives dating British-Australian girls. However this did not stop them from occasionally attending Castellorizan brotherhood dances, Baptisms, and weddings where they were sure to see the available young Castellorizan girls chaperoned by their parents.

" ...those days, you'd go to a wedding and you'd be on one side of Paddington Town Hall and family was on another and you'd see a lass you'd like to dance with and you'd get up and walk towards her and you'd see the mother whisper and you'd ask the mother 'epitrepete'? (Is she permitted?) and if the mother said 'yes' then you'd put your tail between your legs and walk back so that was the relationship those days as far as boy/girl situation was concerned. But I joined the order of AHEPA about 25 years ago... and I was very active in it. I got involved organising balls and conventions etc and when they formed the Ladies Auxiliary, 'Litsa' was one of the foundation officers of it and I got to know her through the order of AHEPA... " (49)

Greek Staff Ball: 6th of April 1940 at the Mark Foyes ball room.

The AHEPA Organisation

However 'Litsa' was not Castellorizan for second generation Castellorizan girls in the late 1930's, 40's and 50's were not allowed to join any of the Greek-Australian organisations such as AHEPA (the Australian Hellenic Educational Progressive Association) which had formed in 1935. (50) AHEPA was patterned after its American namesake, founded in 1922 as a reaction against the nativist and anti-foreign attitudes that prevailed in America during the pre-war years. The organisation was formed in Atlanta, Georgia where the Ku Klux Clan was active and the need for action urgent. Greek-American businessmen who felt the menace of anti-foreign opposition banded together for self-protection.

" It appealed to those who were climbing the economic ladder of success and represented a form of social recognition to those who craved it. AHEPA represented Americanism in a decade when many were anxious to shake off traces of foreignness and become identified with the American community. " (51)

In Australia the organisation was supported by similar people "country shopkeepers in N.S.W. and Queensland", (52) and was first established in Scone, N.S.W. The Australian AHEPANS had similar aims and objectives, "to bridge the gap between Americans and Greeks" (53) and the organisation was formed for similar reasons as its American counterpart. Australian. society was also overrun by severe xenophobic sentiments before the Second World War. Irrespective of the origin of the organisation, it appealed to many of the pre-war second generation because its proceedings were conducted in English. (54) The Sydney AHEPA was made up of, apart from the first generation Greeks, second generation Kytherian boys and girls and Castellorizan boys.

Although Castellorizan boys were given the liberty to socialize freely and involve themselves in organisations such as AHEPA, they also had obligations to the family. The boys were forced to work in the family business out of respect and loyalty to their family. Thus they were encouraged to leave school at an early age usually in first year high school or at the latest after completing the intermediate so they could help in the shop. While still at school and during the school holidays the boys were expected to work in the shop to relieve their parents but this was not a popular activity.

" I hated the school holidays because I worked, we all worked very hard because unless we all pulled together, we had no machines for peeling potatoes in those days we did everything ourselves, nowadays everything comes prepared - we peeled and cut potatoes by hand, we cleaned all our own fish, cooked our own prawns and lobsters - we worked very hard. " (55)

Pre-war Castellorizan family resembled a pre-industrial family, where all the work was done in the home amongst the extended family members. Greek agriculture was primitive, poor and inadequate. Consequently, the Greek rural family was forced to struggle as a unit. (56)

" In the fields there is always work, not only for parents and adult children, but also for little boys and girls. Children, therefore, especially boys are desirable, since they are potential workers and economic assets. In general, the family is characterised by collective economic activities and a]l the well known features that are typical in rural cultures. " (57)

The Castellorizan boys were not usually encouraged to attain professional careers. Instead they were drilled into achieving financial security through working in the family business with their parents.

" ...all Dad could see was for Con to finish his age at school, to bring him in the shop and this was the kind of thought of my parents, and we weren't encouraged in school at all, not at all... " (58)

Many of the young Castellorizan children resented being deprived of an education, "...I suppose if I was to resent my parents it would be for this but then again you can't blame them because I don't think they were brought up to understand this kind of thing any better themselves... " (59) and they emphasized its importance and advantages to their children, the third generation, who were encouraged to pursue professional careers.

" We wanted them to have an education - that's the one thing we stressed upon them... because I didn't have an education and this is what held me back for years - Just getting a good job. " (60)

Castolorizian café in George Street Sydney 1938

Castolorizian family picnic in 1938 at the National Park

Educational Advancement

This was not the only reason the second generation parents stressed educational advancement to their children, it was also to increase the status of the family, not the nuclear but the extended family. "...One nephew is a doctor, another one is in the police force etc. We haven't got a lawyer in the family, that's why we are thinking of making my son one, so we can have all our bills free". (61) Apart from the second generation Castellorizan boys who worked din their parent's business, there were others who attempted to find work outside, in Australian firms and businesses. However in the late 1930's outside employment was virtually impossible to find because a Greek name meant instant refusal.

" I wasn't a brilliant student at school, at that time I was referred to as above, I started from November applying for jobs and I wasn't even getting a reply from the Sydney Morning Herald, I spent days writing out my references because they'd asked for copies of them and each week 'd also write to a bank and an insurance company and I never got one reply whatsoever. And I met this Australian person once and he said 'Bill', well I wasn't called 'Bill' then, 'why don't you change your name'... my name was 'Evangelos Andropoulos'... I looked up the dictionary... and right there was 'Bill Andrews' and lo and behold... I was getting replies to my applications for jobs. And I remember this clearly as anything... Once the 'Bill Andrews', the replies came in, I'd walk into the office and as soon as I did, I could see the reaction, they'd say no way... they'd say we'll let you know and you'd never hear from them again. " (62)

Even though the second generation Castellorizan children were discriminated against in employment they still identified within themselves a dual loyalty, an allegiance to a curiously distinct sub-culture which was neither Greek nor Australian but a strange mixture of both.

" I would say I'm Greek but I would say I'm Australian born... I think it means we're proud of our heritage, very proud of our heritage, I haven't been to Greece yet, I would love to go, but then again I don't think we could live there... " (63)

Most of the second generation were aware that they were different but they were not conscious of constituting a completely new and different culture from their parents, yet they were able to define it rather effectively.

" ...we get on much better with Australian-born Greeks than... the Greeks that just come out here, we get on alright with them of course but there's not as much in common... the same with the Australian friends but the Australian-born Greeks are the ones that we more in common with. " (64)

said Australian-born Castellorizan Mrs. 'Vanessa Politis'. The whole issue is not that the Castellorizan children who were born in Australia were becoming more Australian or less Greek hence 'assimilating', to use the popular pseudo-scientific term, but that they had adapted Greek

Kytherian vs Castellorizans

culture and traditions to suit the Australian environment. They were a "new hybrid Australian" who was just as committed to Australia as the British-Australian. Mrs. 'Stacy Mavromatis' a Castellorizan woman born in Sydney before the war explained that "Well actually deep down I'm Greek I was born in Australia - and...I'm very proud of my heritage." However she passionately exclaimed that

" This is my country - this is where I was born - where I was raised - wherever I wander, wherever I roam... went to Greece I felt that somewhere I belonged - but this is where I really belong - this is where my roots are... " (66)

The second generation Kytherian children had a completely different upbringing from the Castellorizan children. The Kytherian children born and bred in the New South Wales country towns experienced an acceptance which had not been felt by the young city born Castellorizans. The Kytherian children developed a secure self-image in the country towns where the threat of foreigners was not as immediate and where their father was usually highly respected.

" ...the Greek families that were in the town were fairly well respected. And my father was highly respected in that town. He had been there many years. I never ever in my childhood or later on ever struck any prejudice. You know I was never called a dago or anything like that... " (67)

Furthermore, the Kytherian children had what appeared to be a more liberal upbringing compared to the young Castellorizans. However they were still]1 imbued with a feeling of 'Greekness'. The Kytherian first generation parents were equally concerned with making their children aware of their Greek heritage and background and this was done very effectively within the family.

" ...I remember my mother used to come at bedtime and give me (Greek) lessons before going to bed at night and I had an exercise book and I had a text book of some sort... I was taught to do Greek dances by my mother. I was taught to play the piano...and my mother would buy Greek sheet music ...the national anthem. " (68)

The Kytherian children were made to feel 'Greek' by their parent, not the towns-people nor the other British-Australian children. Whereas the Castellorizan children in Sydney were male aware of the fact that they were Greek not only by their family but also by the prejudice

displayed by the wider Australian society. Kytherian 'Alexandra Coronias' born in Tenterfield, N.S.W. in 1934 describes how she became aware of her Greek background.

" ...I felt Greek because my parents made me feel Greek not because the townspeople did. In that I wasn't allowed the same freedom that my friends had. I could go to Sunday school and church which I did - all the churches in fact but I went to the Anglican Sunday school and in fact I was confirmed in the Church of England Church. But I was not allowed to go to Sunday School Picnics. I was allowed to invite my friends home to play and they all used to come and play because we had a big garden and it was in the center of town and everything was all quite comfortable but I was not allowed to go to their place to play. I could invite my friends home to have meals but I wasn't allowed to go to their place to have a meal or to stay overnight. " (69)

Although Kytherian second generation children were inculcated with the concept of being 'Greek' in a less obvious way from the Castellorizan children, it was still equally effective.

Furthermore, unlike the Castellorizan children, the Kytherians were not usually required to work in the family business, though some did. The shop usually had sufficient staff in the 1930's and 40's not to necessitate the assistance of the entire family. Thus while the Castellorizan children were required to stop school early to help in the shop the Kytherian children were pushed into professional careers and the importance of educational advancement was constantly stressed to them "...we were forced to study, forced to do well at school," explained Kytherian 'David Mavros' born in Bega, N.S.W. in 1953, "...we had the pressure on us that if we didn't do well, well you know all hell would break loose, and also the fact was pushed on us that they don't want us to end up like our parents were..." (70)

Although Kytherian children were allowed to participate in church activity in the country towns they were not allowed to socialize at night with their friends. The girls in particular were not allowed out to dances with their British-Australian girlfriends. 33 year old Kytherian 'Helen Kiriakos' born in Grafton, N.S.W. explained

" ...I think I had a strict upbringing because of my Greek background, we weren't allowed to do what our Australian friends were doing... By the time I left Grafton I was in my teens, 15 and my friends were all going to dances by themselves and I was never allowed. Whatever I did was supervised properly... " (71)

Kytherian Christening Lockhart N.S.W. 1933

The staff of a café Tenterfield N.S.W. have a picinic 1937-1938

In the early years the Kytherian children, like the Castellorizan had to participate in family picnics which they also enjoyed. 'Alexandra Coronias' discussing the family picnics she participated in at Tenterfield, N.S W. in the late 1930's and early 40's explained that...there must have been at least four families. Perhaps five. The children of those families were older. I was the youngest. We would go on picnics. Lovely picnics. Out of town by a creek. We'd take a portable record player and play Greek records. I always heard Greek music. My mother loved Greek music. We'd play Greek records on this portable record player And it was very enjoyable! I loved it! At the age of eleven 'Alexandra Coronias' enjoyed the family activities but she would have started resenting them if she was still in the country town during her teenage years. In Sydney the Castellorizan children could at least go with their parents to brotherhood dances and picnics where they could meet other young people. However as soon as Kytherian children completed their schooling in the country towns they were brought down to Sydney. Once in Sydney their entire social life radically changed. They were encouraged to participate in the Greek church, attend Greek school if possible and mix with other Kytherians in the Greek social organisation which had formed. The parents did not restrict or control their children's activity in Sydney as they had done in the country town. Both Kytherian boys and girls were allowed out in groups particularly to attend the functions of the Greek social organisations such as AHEPA. Gillian Bottomley in her study of second generation Greeks in Sydney described these organisations as "useful as a kind of marriage market". (72) She explained that,

" In this setting, young people maximize the possibility of falling in love with someone who will also fulfil the requirements of a similar ethnic background, a shared religion and an equivalent socio-economic status. " (73)

The Kytherian parents insisted that their children restrict their social life to a Greek circle in an effort to ensure that they marry a Greek. Thus they were encouraged to join these organisations for the parents had come down for "...the Greekness of ,Ilene, that was the reason...they would have had three daughters in an Australian environment and I think, really they would have liked us in a Greek environment... ". (74) However the parents not only wanted their children to marry a Greek but a Kytherian. One young Kytherian exclaimed that his parents and relatives had been very resentful of him marrying a Greek girl from the Peloponesse.

He explains that this was because the Kytherian parents having been very successful as businessmen wanted their children to keep the money within the Kytherian community, (75) for the Kytherians represented and represent the Greek moneyed elite in post-war Australia. Apart from the emphasis on retaining money within one particular group in society, the young man's comment also displays the regionalism which pervades the Greek community in Australia and also throughout Greece. Besides the Kytherian community, regionalism is also evident within the other groups of Greeks in Australia. The Castellorizan parents also felt the same way, and preferred if not demanded that their second generation children marry other Greeks who were descended from the same island. If they did not, then the non-Castellorizan wife or husband would experience a subtle form of rejection from the community. One second generation Greek woman married to a second generation Castellorizan man commented

" I feel... although its not quite open how they feel towards you, some of the older Casie (76) generation still tend to make you feel as if you're a 'xeni' (foreigner)... When I got engaged to 'Bill' we went to visit a family... relations of 'Bill's' yet they couldn't come to the engagement. I walked in, the introduction was made, and the old lady, the grandmother turned around and said to 'Bill' 'Oh well it doesn't matter. You didn't marry a Casie but she looks like a Casie.' Well that made me feel dreadful,...and over the years you hear them say, 'Oh who did so and so marry?, Oh he married a 'xeni'...Even though the woman may be Greek...She's referred to as a 'xeni'...we've been married twenty years now...but... I still get the feeling at times that they don't really consider me a Casie. I'm still a 'xeni' (foreigner)... they consider me Greek, but they don't make you feel, 'yes, you are completely one of them.' " (77)

A first generation Greek woman who had married a first generation Kytherian man also experienced similar rejection from the Kytherian community and had this to say,

" Usually the Kytherians have one failing, very bad failing due to naivete, it is not only here but they have it on their island when they marry someone from another village, from inside of Kythera...they would say that he married a 'xeni' because he didn't marry someone from the same village. " (78)

In pre-war Australia, especially before the 1920's, and 30's when there were very few available Kytherian women, the Kytherian community did not like but nevertheless accepted, the Kytherian men who married British-Australian women, for it was understood that they had no choice. But

The Olympic club formed at Sydney University 1952.